In Retrospect

A look back on a trip taken to take a look back.

I am at my uncle’s grave. He is buried on top of his mother, who is buried on top of a woman no one can identify. His name is not on their headstone.

To the left: a row of headstones, each a few inches apart. To the right: an empty spot, then more headstones. It is still, except for an inconsolable man several rows behind me, the distant sound of trains pulling into and out of Broadway Junction, and the shhhhhh of air being compressed by cars as they drive down the Jackie Robinson Parkway.

I observe the man. His family holds him. He quiets until your eyes reach this comma, then falls back to his knees, face on the ground. This happens several times. I wonder who it is: mother, or child?

My attention drifts. Beyond the man and his family is an expanse of impeccably kept grass and trees stretching to sunrise. Toward sunset is an escarpment. It’s not quite high enough for the treetops to hide the houses, but back in 1849, it must’ve been green all the way to the horizon. Wealthy people used to picnic in cemeteries before cities created public parks. It isn’t hard to see why.

It also explains the end of Our Town. In the third act, the dead, buried near the town, chat amongst themselves about the goings on of those still living. Some of the living stop by to visit. The dead are, in a way, still part of the community. When public parks came into existence, people stopped visiting as often. Now, we are distant, disconnected from our loved ones who have died. Or is just me?

The last time I was here, I was ten years old. I only remember sitting in a car, the yellow warning signs as we slowly slalomed through the parkway’s twenty-five mile per hour zone, and sadness. I half remember clouds. I don’t remember the service or the casket being lowered into the ground. Mom says I saw it and that my reaction to this event caused me so much distress that I ended up in therapy.

I remember bits and pieces of therapy. Miss Joyner was nice. After her was a white guy with a bushy mustache whose name escapes me. I refused to speak with him because, by that time, twelve year old me would say there was nothing wrong. I had told Miss Joyner everything — I wasn’t upset about my uncle; I didn’t want mom to die. To pass the time, I asked him to teach me how to play chess.

As time passes, I think about the difference between myself and the man. I feel nothing. But I must have: after my uncle’s, I avoided funerals for thirty years until a nephew I helped raise passed away. Had I visited him, a stranger might instead be wondering about me right now. After all, I ran through a box of tissues at his funeral. But a few decades is probably too long to feel something for someone you don’t remember.

The man is still visibly upset. I wonder if he (and, by extension, we) would be less heartbroken if our loved ones were buried closer to home? What if it is his child but it’s 1849 instead of 2022? Is a child’s death easier to accept in a world with both high birth and child mortality rates? Was the familiarity of death before modern medicine the reason why only an apparent handful of 6,500 languages have a word for parent who has lost a child?

A car pulls up to my left. A few people get out and spend time at the large family memorial near the road. Their mood is less solemn and more routine. I watch as they enjoy the weather and each other’s company, but not so much that one would expect to see a picnic basket.

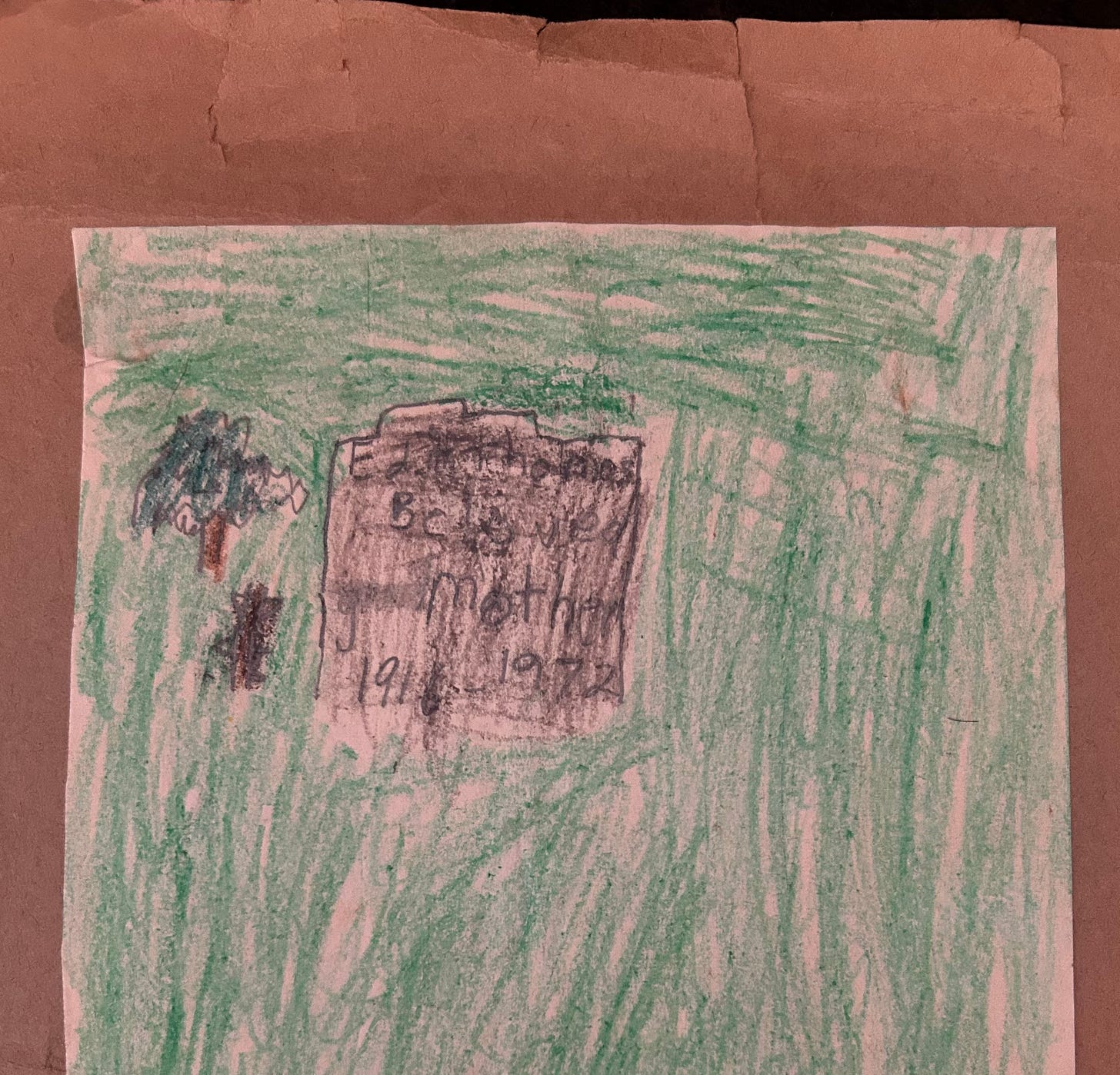

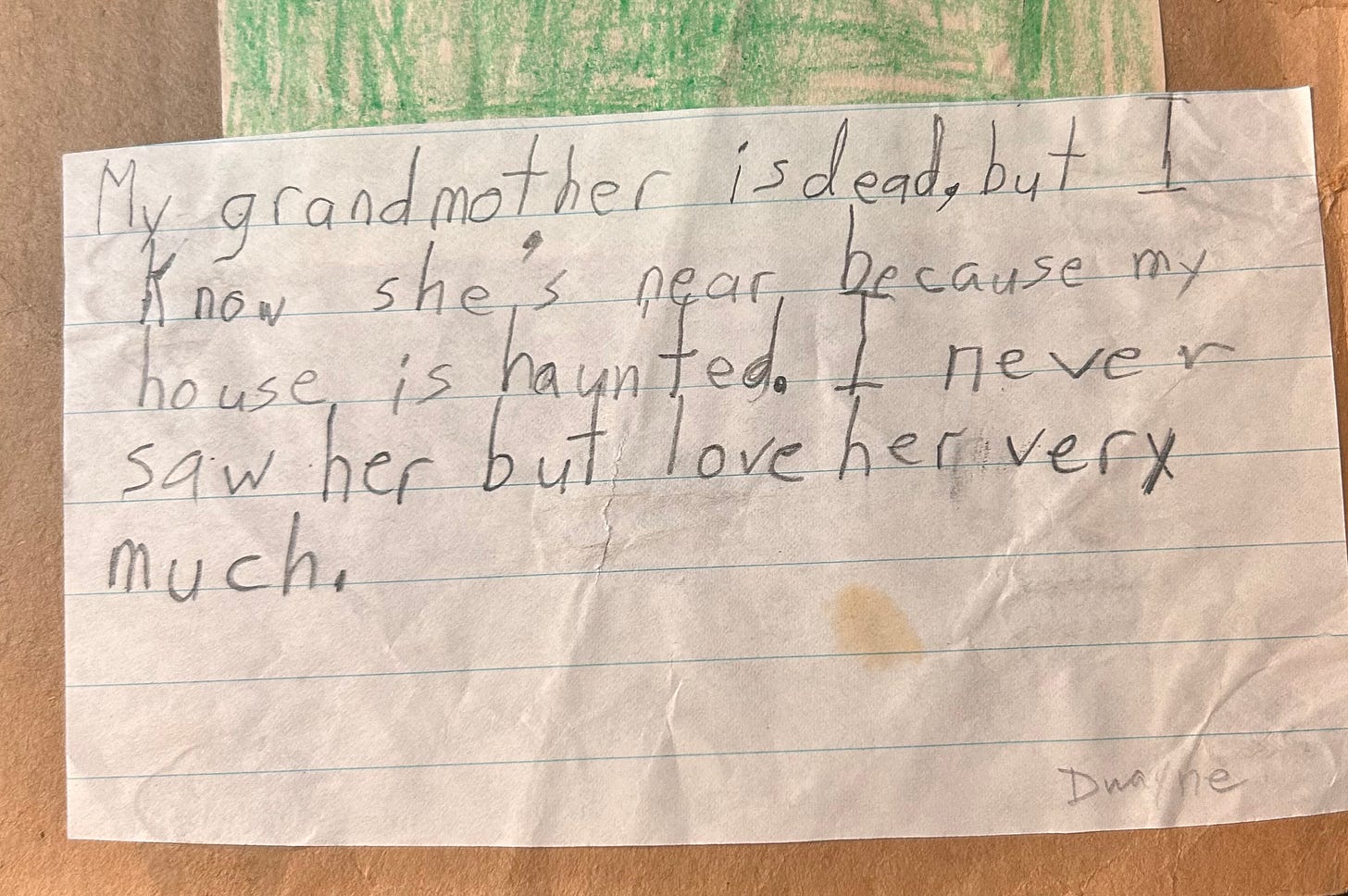

Three years later, I finally sit down to write what you’re reading now. Mom is cleaning out a closet and hands me some of my stuff from elementary school. Among the artifacts is a picture I drew of my grandmother’s grave. Six-year old me’s caption: